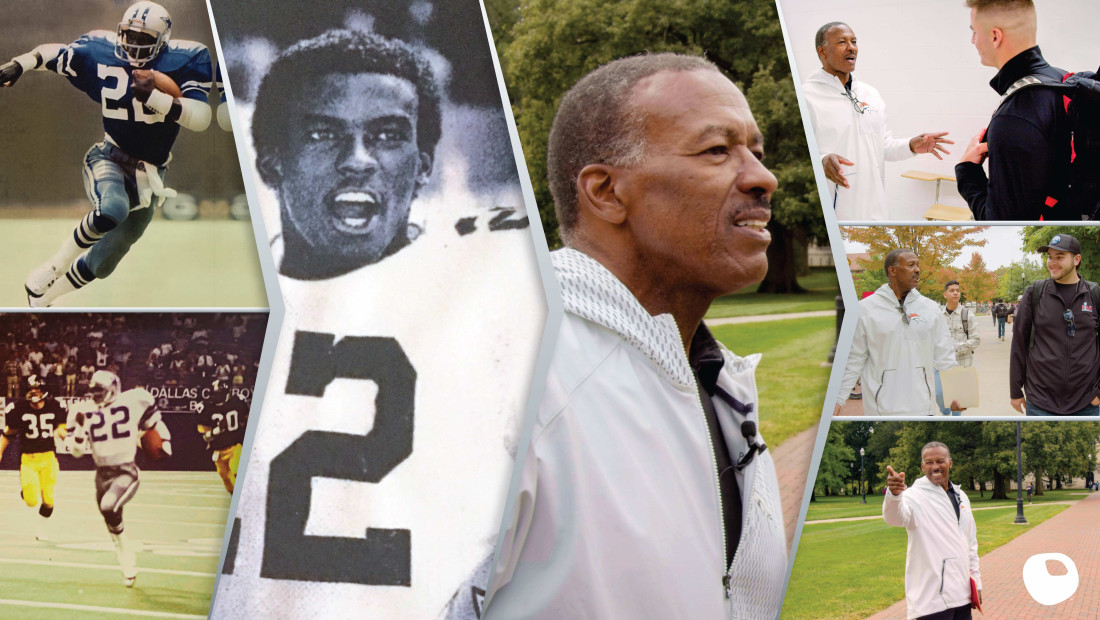

To illustrate Wade Manning’s sheer tenacity — his almost reckless fearlessness — one must set the scene. Manning is deep in the defensive backfield in Canton, Ohio, on a muggy day in July 1979, several months after graduating from The Ohio State University with a degree in physical education.

“Do you know how afraid I could have been in the Hall of Fame Game when Coach (Tom) Landry said, ‘You’re first up on punt return’?” Manning recalled.

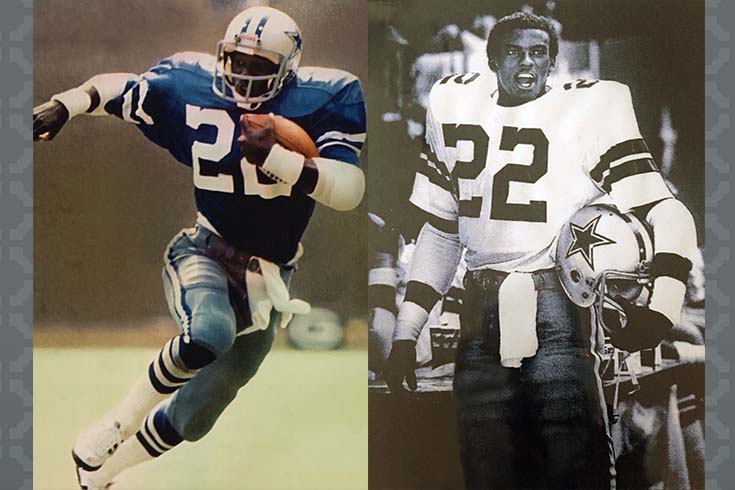

Fear would have been the intrinsic response for almost anyone. But this was professional football, Dallas Cowboy style. So, punter Ray Guy of the Oakland Raiders launched the ball 58 yards and Manning caught it with ease.

“Now I got 11 guys coming down field trying to take my head off,” he said. “I could have been scared out of my mind. But I wasn't. … There was a calm inside of me. That was ridiculous.”

Ridiculous because — other than on an intramural team — Manning had never played college football. What’s more, he only played one football game in high school, after injuries knocked him out in a scrimmage his sophomore year and again after one game his senior year. At Ohio State, Manning was a centerfield baseball player and a sprinter for the track team but was never considered for Woody Hayes’ team.

Was this outfielder/sprinter-turned-rookie-returner out of his mind? Maybe, Manning says today, but he knew his strengths. Apparently, the Cowboys scouting staff did, too.

“I knew that I was a world class sprinter,” Manning said during an Ohio State visit last fall. “And my whole mindset was, ‘Boy, are they in trouble. Because when I catch this ball, they gotta chase me.’ Versus, ‘Oh, I hope I don't miss this ball. I hope I catch this ball.’ No.”

“I only believed in what I had already accomplished,” he said. “I was fast.”

A spinning top among Cyclopes

Fast doesn’t fully describe what happened when Manning caught the ball. In that first Hall of Fame game, he returned the ball 42 yards, breaking four tackles. Years after his NFL career ended, someone sent Manning video clips of his characteristic runs for Dallas and for the Denver Broncos, with whom he played 1981-83. He shares the videos on his cell phone now, and onlookers cheer.

In a film reel of another Raiders game, this time in 1981 when Manning was a Broncos receiver, he looks like a pinball ricocheting off defenders who stumble in his wake. No. 75? That’s defensive end and Hall of Famer Howie Long — all 6’5” and 285 lbs. of him — taking a tumble, too.

“He was a rookie then. When I made that first spin, while I was spinning, I picked him up in my peripheral vision,” Manning said, reenacting the scene 42 years later, twirling right and then left. “So, I've picked his left shoulder to spin off of. He's running as fast as he can. He believes I don't see him so … I'm going to get this big hit — ooomf!”

But Long missed. So did eight other defensive players.

Ohio State kinesiology professor Jackie Goodway was stunned when she saw one video, and now shows it to her students to showcase superb motor coordination. “The precision with which Wade moves is remarkable. ... His ability to change direction at great speeds with no disruption to the smoothness of his motor pattern is a testament to his skill and ability,” Goodway said.

Even in his first game in Canton, the Ohio State centerfielder who doubled as a sprinter waylaid career players.

Beating the odds and stunted growth

Manning’s parents both worked factory jobs. He recalls his father coming home each night exhausted and covered in steel dust.

“He only said this to me one time — that's all it took: ‘If you don't want to go in the steel mill, you'll need to get an education.’ From that point on, I never missed a homework assignment.”

As a high school junior, Manning was 5’1,’’ so small that family and friends called him “Bird.” The culprit, he figures, was a ruptured appendix in ninth grade; doctors didn’t discover it until days later.

“They told my mom to get ready for a funeral because there was no way that I would survive this,” he said. “I had peritonitis in my stomach, gangrene, and they said, we'll do what we can.”

He survived but dropped to 82 pounds, he said. He would play several sports in high school, but he didn’t gain much height until just before his senior year. Then, in one calendar year, he grew 10 inches and topped 190 pounds. When he put on pants after having worn only shorts and baseball knickers all summer, he said, “I looked like Jethro Bodine from the Beverly Hillbillies.”

He wanted to attend college, but the money wasn’t there. So, after high school, Manning worked in the mailroom of an engineering firm that paid for night classes as long as he made A’s and B’s. When someone noticed his scores in math and science, they helped him get an engineering scholarship at Ohio State.

On his first day of classes, he could have been intimidated by a university so large. Instead, he walked to the center of the campus Oval, turned to face the statue of William Oxley Thompson, and made a proclamation.

“I said it out loud, right there: ‘Nobody knows who I am. But before I leave here, everybody's going to know.’ And then I walked across and went to Arps to go to my first class.”

Feeling powerful, believing in himself

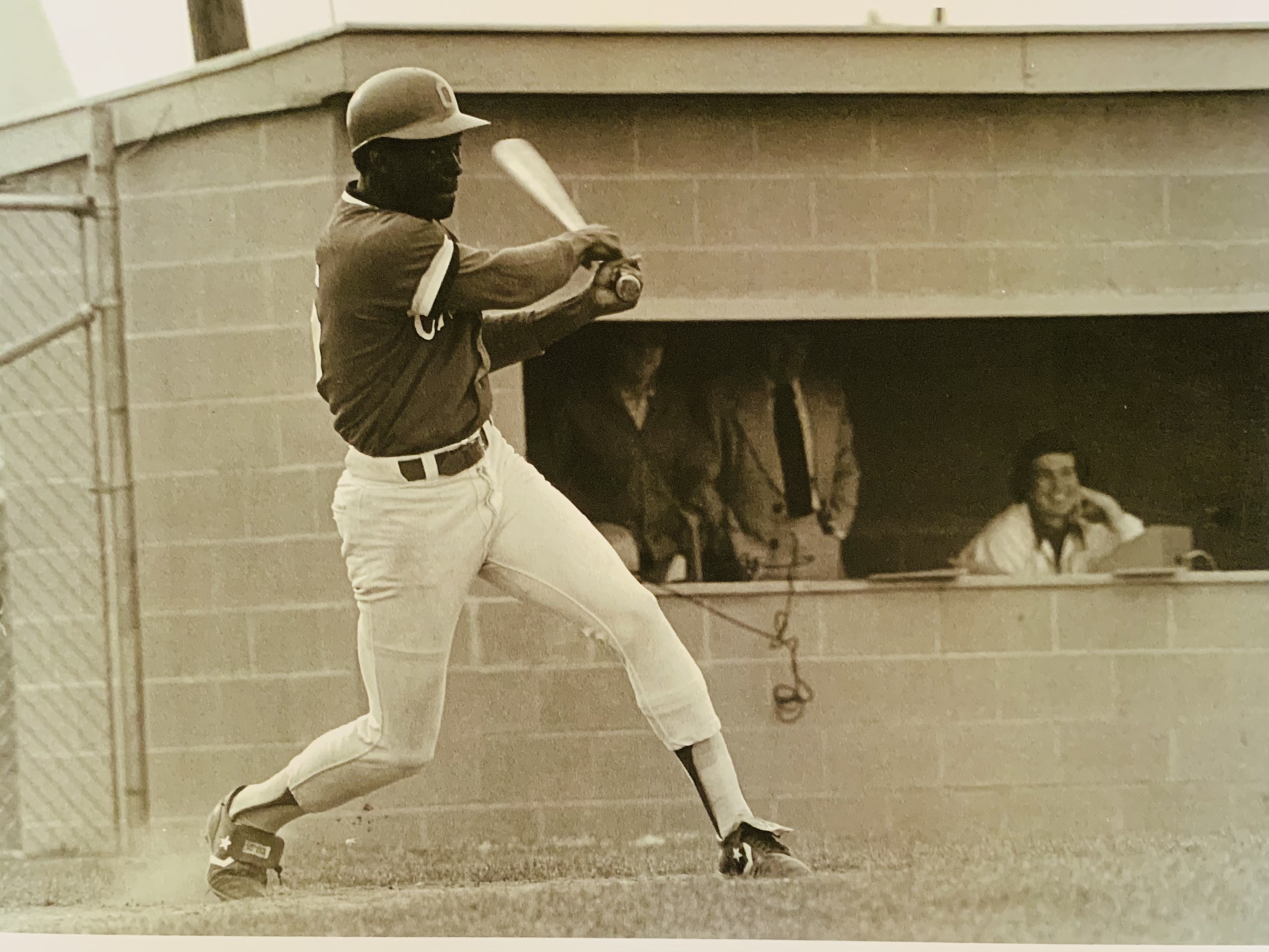

Manning had always played baseball, and as a kid, he sprinted city blocks in Shaker Heights to get where he needed to be. Now, he had the girth to swing the bat with purpose, so he walked on to Ohio State’s baseball team and soon got a scholarship to play.

He was known for stealing bases (44 in his college career) and hitting homeruns. Sometimes he socked balls far out of the park, according to the Lantern: “Wade Manning probably had the hardest hit of the day when he led off the game with a 450-foot home run over the left centerfield fence. ‘That's one of the longest hit balls I have seen,’ (Coach Richard) Finn said.”

Manning was flexing his newfound muscle.

“I felt powerful,” he said. “I was just so strong.” Before he came to Ohio State, he said, “I had never hit a homerun over the fence, (only one) inside the park. And all sudden I'm launching these things.”

About this time, Manning took on another major. Professional sports were a dream, but he was realistic. The average professional athlete only plays 3.3 years. Manning needed a career afterward that he could see himself in.

Learning the mechanics of physical activity

He wanted to educate kids and help them excel athletically, so he began to study physical education. The program was rigorous, requiring him to add chemistry, physiology and anatomy classes to his already-packed schedule. But as he immersed himself in the coursework, he began to better understand how his body behaved when he swung the bat or stole bases.

“You had an opportunity to learn about muscles and bones and nervous system,” he said. “And then you had a chance to look at the physiology of how we make energy. … And then you go into this kinesiology class, and you're learning about the science of body movement and motion.”

He changed his diet, rejecting sugary snacks given to players. His studies enhanced his understanding of his performance.

“This type of fast-twitch, slow-twitch (muscle), the length of my femur, the length of my tibia, and the nervous system does this. And then your mitochondria are doing this. I mean, it just all meshes for you to be able to dance, jump, dunk a basketball, fake somebody out, stop and start.”

When a roommate on the track team challenged him to a race, Manning accepted, and ended up walking on to that team as well. Now, in his senior year, he was playing two varsity sports in the same season.

If it weren’t for his time in track, he said, “there is no way that I would have tried to play NFL football, because I thought you had to be Superman in order to play football. But after doing … track workouts and running in those track meets, I did not believe that football could be as hard as this.”

Breaking free of obstacles

The endurance and perseverance he gained in class and on the track perfectly prepared him for what many thought was a longshot: A winning performance at Ohio State’s NFL Training Day (now called Pro Day), when scouts from around the country come to see college athletes in action.

One or two coaches had alerted pro teams to Manning’s speed. The Cowboys were known to sign players with no college football experience, including college basketball forward Cornell Green and center-forward Pete Gent, who later wrote North Dallas Forty. That winter day in the French Field House, Manning blazed across the track. “I ran the 40-yard dash that day, and I ran 4.23 seconds … which was unheard of. And two days later, I signed a free agent contract with the Dallas Cowboys,” he said.

Manning began to spin, dodge and fake out defenders as a punt returner for Dallas and then as a wide receiver after being traded to the Denver Broncos.

Sportscasters had plenty to say: “Look at him go! He’s got some running room! 40, 50! .... Wade Manning may have just made himself a pair of Dallas spurs. Sixty-yard return by Manning, the free-agent rookie.

“Wade Manning just shows them his heels...”

“Wade Manning. An outstanding run on this play. Look at all the people that had the opportunity to make the tackle on him. He’s breaking all of those tackles.”

His education stayed with him

Despite his success, four years into his career, a doctor picked up on an eye injury that Manning had received years earlier when a friend tossed a football dummy at him. A wood handle broke a facial bone and damaged the muscle surrounding his eye, limiting its range of motion. The resulting surgery kept him from playing high school football then. For years, he said, he disguised the injury during physicals. Now it knocked him out of contention for the pros. His theory about not having a long-term sports career proved spot on.

“Education is not something that you fall back on,” he said. “I heard that for years from athletes. ... ‘I'm going to get my education to fall back on just in case I don't make it to the pros.’ No. You’ve got to get your education because you're going to live a lot more years — trying to take care of yourself and your family — than you'll ever be playing your sport. It's going to be a glorious time if it happens to you. But it's short.”

He taught health education for 29 years, mostly to high schoolers. One can imagine Manning the Teacher regaling high schoolers with stories from his glory days as Manning the Wide Receiver. But as a teacher passionate about fitness and nutrition, he also lectured on the fallacy of food pyramids and the way insulin receptors in fiber protect the body from cholesterol. He still talks a blue streak about how processed foods are depleted of vitamins and minerals and how the body burns body fat for energy only after glucose runs low.

In the end, his education at Ohio State proved even more impactful than his athletic achievement.

“My mom went to the eighth grade; my dad graduated from high school. I broke that chain,” he said. He wants students to believe in the “impossible” — to make their own proclamations on the Oval. Speaking to kinesiology students in September, he told them living up to the “The” in Ohio State’s name means being fearless.

“You have to believe in your successes, and you can overcome the fear,” he said. “You've had too many successes along the way. You know you can do it. So, you do it.”